|

|

|

Museum hosts Sprague family reception

|

| "Frank J. Sprague: Inventor, Scientist, Engineer" |

The museum was honored to receive several dozen descendants

of Frank J. Sprague and their guests at a private reception

on May 15, 1999 for the opening of a new permanent exhibit:

"Frank J. Sprague: Inventor, Scientist, Engineer".

|

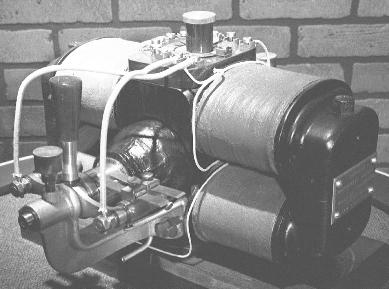

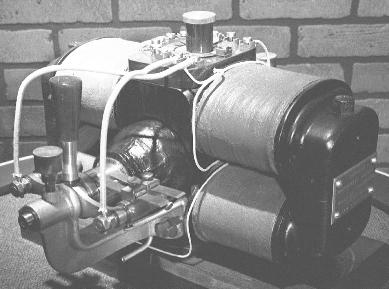

The centerpiece of this exhibit is what we believe to be

the oldest surviving Sprague motor. As reported previously,

this motor came to the museum

in the spring of 1998 as part of a donation of artifacts,

photographs and documents made to the museum by the Sprague family.

Exhibits Director Fred Sherwood has spent the last year carefully

restoring the motor and documenting its construction.

The motor in question is not a railway motor. It is a small

industrial motor, constructed by Frank J. Sprague in 1884.

At the time, the use of electrical motors to power industrial

equipment was still experimental. Most equipment, such as looms,

presses, mixers, pumps and conveyors was operated either by

hand power, water power (where the factory was near a body

of moving water) or small stationary steam engines.

The Edison system centralized the energy-producing apparatus at

a large, distant powerplant and distributed the energy as

electricity via wires. Electric motors could be used in

factory/industrial applications, powered by these wires, and

thus obviating the need for a boiler and the attendant heat,

noise and wasted floorspace in each factory.

Frank J. Sprague (1857-1934), a native of Milford, Connecticut,

graduated from the Naval Academy in 1878. After completing

several tours, he signed on with the Thomas Edison's firm in May 1883.

One of Sprague's significant contributions to the Edison Laboratory

was the introduction of mathematical methods. Prior to his arrival,

Edison conducted many costly trial-and-error experiments.

Sprague's approach was to calculate using mathematics the optimum

parameters and thus save much needless tinkering.

Sprague's stay with Edison was brief; in 1884 he left to form the Sprague

Electric Railway and Motor Co.

Sprague's development of his industrial motor was evolutionary,

not revolutionary. He carefully studied the cutting-edge of

motor development and came up with a line of well-engineered

motors that were reliable and efficient. We believe the 1884

motor was a demonstration prototype. If so, it is one of the

motors Sprague brought to the Philadelphia Exposition in the

summer of 1884, a lucrative outing for Sprague, netting several orders.

|

| The 1884 Sprague motor |

The industrial motor business continued to be very profitable for

Sprague throughout the 1880s, and it was this profit which in effect provided

the R&D funding for him to pursue the study of railway electric

motor applications, eventually leading to what is considered to be

the first commercially successful electric streetcar line in Richmond,

Virgina, 1888. Although the line was a financial success for its

owners, the first to prove more profitable than animal-powered street

railways, Sprague himself lost a considerable amount of money on the deal.

He was unable to meet the deadline specified in the contract because

the trackwork, which was performed by another subcontractor, was shoddy.

Sprague had expected a maximum 8% grade when he, not yet having

seen the Richmond site, negotiated the contract. The actual grades

were higher than 10% however, and the curves were sharp and unguarded.

Sprague's initial equipment was unable to produce enough tractive

effort to function under these conditions, and therefore he was forced

to go back to the drawing board and re-design using double-reduction

gearing. Sprague had to renegotiate the contract down from the initial

$110,000 to $90,000, of which only half was payable in cash, the other

half being stock. Sprague's expenses, increased by the re-engineering

and manufacturing costs, were $160,000, yielding a

cash loss of approximately $115,000, which, in 1999 dollars, would

represent about $1.2 million. Sprague's ongoing success with his

industrial motor business was important in maintaining his financial

solvency during this period.

Sprague continued in the electric railway business for several years and

built several dozen lines. Facing competition from the large and

financially well-equipped Thompson-Houston company, which had purchased

fellow street-railway pioneer Charles Van Depole's firm, Sprague was forced

to sell out to Edison General Electric in 1889. What Sprague perceived

to be a deliberate effort to remove his name from the street railway

division led, in part, to his departure from that company.

Sprague began work on yet another electric motor application: elevators.

Heretofore, elevators had been powered either by steam or

hydraulic systems. Sprague developed a method whereby an electric

motor, mounted at the top of the shaft, directly hoisted and lowered

the elevator car. The operation of this motor was controlled by

a person stationed inside the car. Because the amount of power

needed to run the hoist motor could not feasibly be carried from

the car to the motor via the long "traveler cable", Sprague devised

a remote-control using relays.

A relay is an electrical switch which is operated via an electromagnet.

The movement of the operator's handle in the car supplies the small amount

of power necessary to energize the electromagnet of a relay which is

located near the hoist motor. The relay in turn controls the much larger

amount of power needed to run the motor.

Sprague's first electric elevator installation was in New York City

in 1893. By 1896, he had completed 33 installations, and then

sold his electric elevator business to a consortium of

companies which eventually became Otis Elevator. From his work on

electric elevators, Sprague came upon in 1897 what is considered to be his

most unique and significant invention: multiple-unit control.

Up to that point, all trains were operated with locomotives, which

supplied tractive effort, and trailer cars in which the passengers or

freight were placed. Because they had to pull a train of "dead

weight", locomotives were of necessity large, heavy machines.

In the multiple-unit system, each car of the train carries electric

traction motors. By means of relays energized by train-line wires,

the engineer or motorman commands all of the traction motors in the

train to behave in unison. There is no need for locomotives, so every

car in the train can generate revenue. Furthermore, higher

acceleration and speed are possible as compared to the locomotive system.

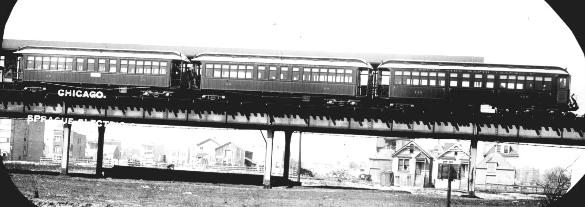

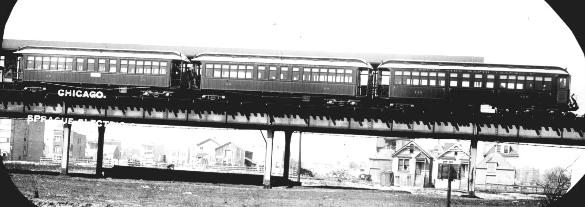

Sprague's first multiple-unit order was from the South Side Elevated

in Chicago. John L. Sprague shared a letter with us relating the experiences

of the representative from General Electric, who had also come out

to Chicago to bid on the project. G.E.'s proposal was for an electric

locomotive system, but when Sprague arrived on the scene, G.E. knew

he had them beat with his superior M-U system.

|

| Chicago South Side El. |

Sprague soon followed with substantial multiple-unit contracts in

Brooklyn and Boston. Quickly, however, competitors General Electric

and Westinghouse both came out with multiple-unit systems.

Sprague waged a successful patent suit in which his controlling patent

was upheld, effectively granting him what we would call today the

intellectual property rights to the multiple-unit idea itself.

Sprague sold his company to General Electric in 1902, and with it the

rights to M-U. He remained a consulting engineer with G.E. into the 1920s.

His activities in the 20th century included the electrification of

the New York Central Railroad, serving on the Naval Consulting Board

during the Great War (W.W. I), work on automatic train control, and

electric signs that could be programmed to display different messages.

Sprague's inventions over 100 years ago

made possible modern "light rail" and rapid transit systems which

still function on the same principles today.

All of this has its roots in the Sprague motor now on display.

These details of the early career of Frank J. Sprague were provided

by Erwin C. Pantel, a member of the museum, who is currently doing his

graduate studies on Frank J. Sprague. Mr. Pantel gave a paper

at the opening, choreographed by slide projectionist and Exhibits Director

Fred Sherwood, on this subject matter.

After the presentation, Mr. John L. Sprague, son of Robert Sprague

and grandson of Frank J. Sprague, shared some letters from his

personal collection on Frank Sprague. Then John joined Peter Sprague,

son of Julian Sprague and grandson of Frank J. Sprague, in cutting

the ribbon and starting the 1884 Sprague motor much to the delight of

all in attendance.

|

| l-r: F. Sherwood,P. Sprague,J. Sprague |

Three generations of Spragues were present at the opening. For some,

it was their first visit to the museum, while others remembered the

dedication of the Sprague Building in 1959,

made possible by a gift

from Harriet Sprague, the widow of Frank J. Sprague.

Within minutes of the the conclusion of his talk, Mr. Pantel received

offers from several Sprague family members to view additional materials

in their collections in furtherance of his research. The museum's

board and staff look forward to continuing collaboration with the Spragues.